The Davao Writers Guild mourns the passing of our founding member, Aida Rivera-Ford, who died on January 17, 2026, just days before what would have been her 100th birthday.

Born in Jolo, Sulu, on January 22, 1926, to Judge Pablo Rivera and Lourdes Consunji, Aida Rivera-Ford devoted her life to literature, education, and the arts. Her literary career spanned more than seven decades, leaving an indelible mark on Philippine literature, particularly through her celebrated short stories “The Chieftest Mourner” and “Love in the Cornhusks,” which have been anthologized both in the Philippines and internationally. She belonged to a generation that shaped Philippine postwar writing and helped establish regional literature as a vital part of the national imagination.

A cum laude graduate of Silliman University with a degree in English in 1949, she served as the first editor of Sands and Coral, the university’s literary magazine. She later earned her master’s degree in English language and literature from the University of Michigan on a Fulbright grant and was a fellow at the East-West Center Culture Learning Institute at the University of Hawaii in 1978.

Rivera-Ford’s dedication to education took her from Mindanao Colleges to the University of Maryland Armed Forces School, and eventually to Ateneo de Davao University, where she served as chairperson of the Humanities Division from 1969 to 1980.

Her published works include Now and at the Hour and Other Stories (1958), which won the Jules and Avery Hopwood Award at the University of Michigan in 1954; Born in the Year 1900 and Other Stories (1997); Oyanguren: Forgotten Founder of Davao (2010); Aida Rivera-Ford: Collected Works (2012); and Heroes in Love: Four Plays (2012). She also co-edited the Mindanao issue of Ani, the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ quarterly literary journal. Beyond her writing, Rivera-Ford was deeply involved in theater, directing and acting with Philippine Theatre Davao and composing the operetta Datu Bago.

Her contributions earned her numerous honors, including the Datu Bago Award (1982), the Philippine Government Parangal for Writers (1991), the Outstanding Sillimanian Award (1993), National Fellow for Fiction at the UP Creative Writing Center (1993–94), and the Taboan Literary Award from the National Commission on Culture and the Arts (2011).

In 1980, Rivera-Ford co-founded the Ford Academy of the Arts (originally the Learning Center of the Arts), and in 1999, she helped establish the Davao Writers Guild.

Her wake and memorial tribute will be held at Ateneo de Davao University on Thursday, January 22, 2026.

Aida Rivera-Ford’s legacy lives on through her stories, her students, and the countless lives she touched through her art and generosity of spirit. She will be deeply missed.

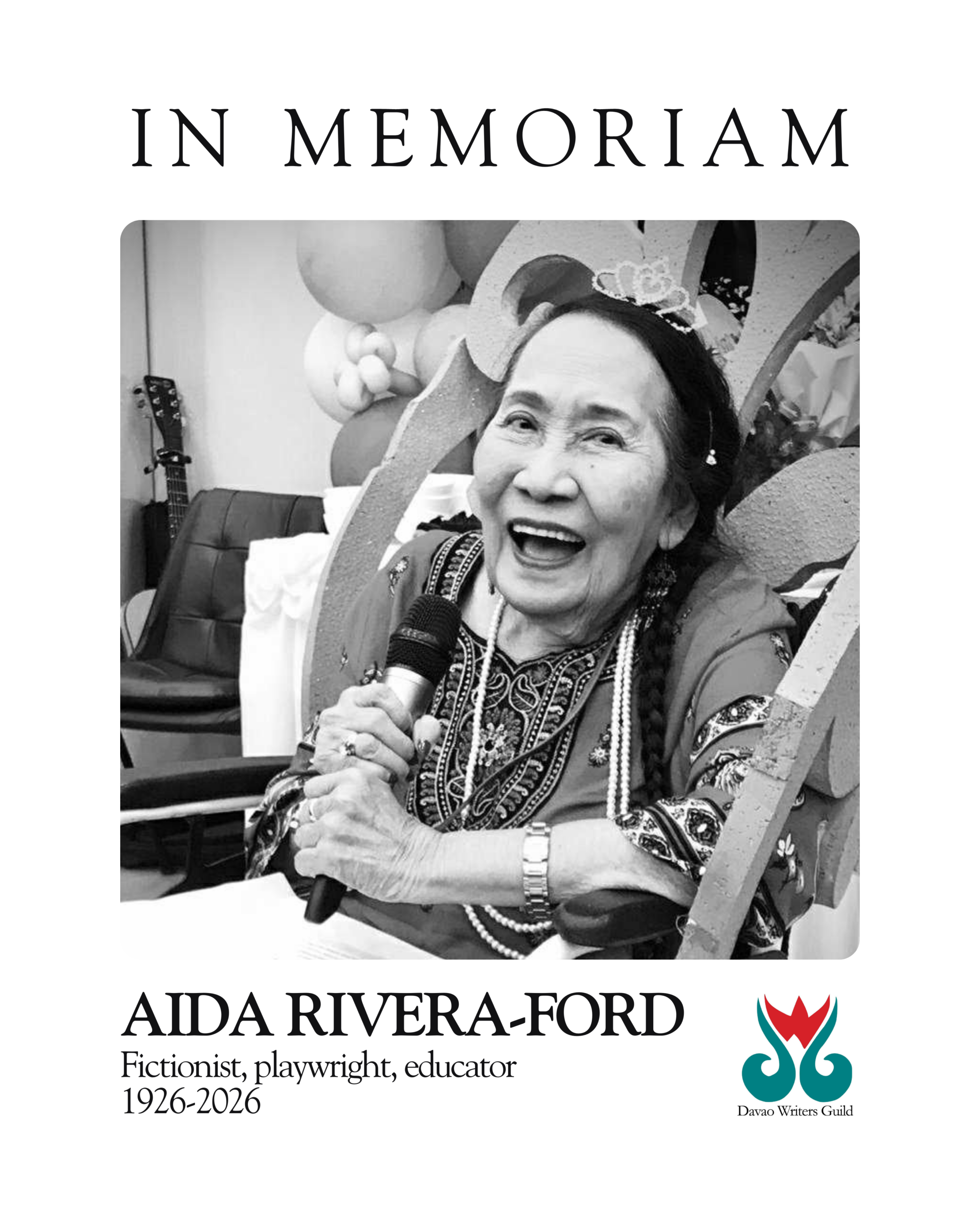

(Information for this notice is drawn primarily from the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, Vol. 12, 2nd edition, 2017. Photo taken January 22, 2020, on Aida Rivera-Ford’s 94th birthday.)